I'm kind of busy these days. Even as my country hurtles toward perhaps the most important Presidential election of my lifetime, I'm spending my time helping my wife run for the Michigan State House and preparing my startup company to announce and demonstrate its product for the first time shortly after the election. At 67, I don't think I've ever had more to do. So why is it that I can barely think about anything except the debut of the Wicked movie later this month?

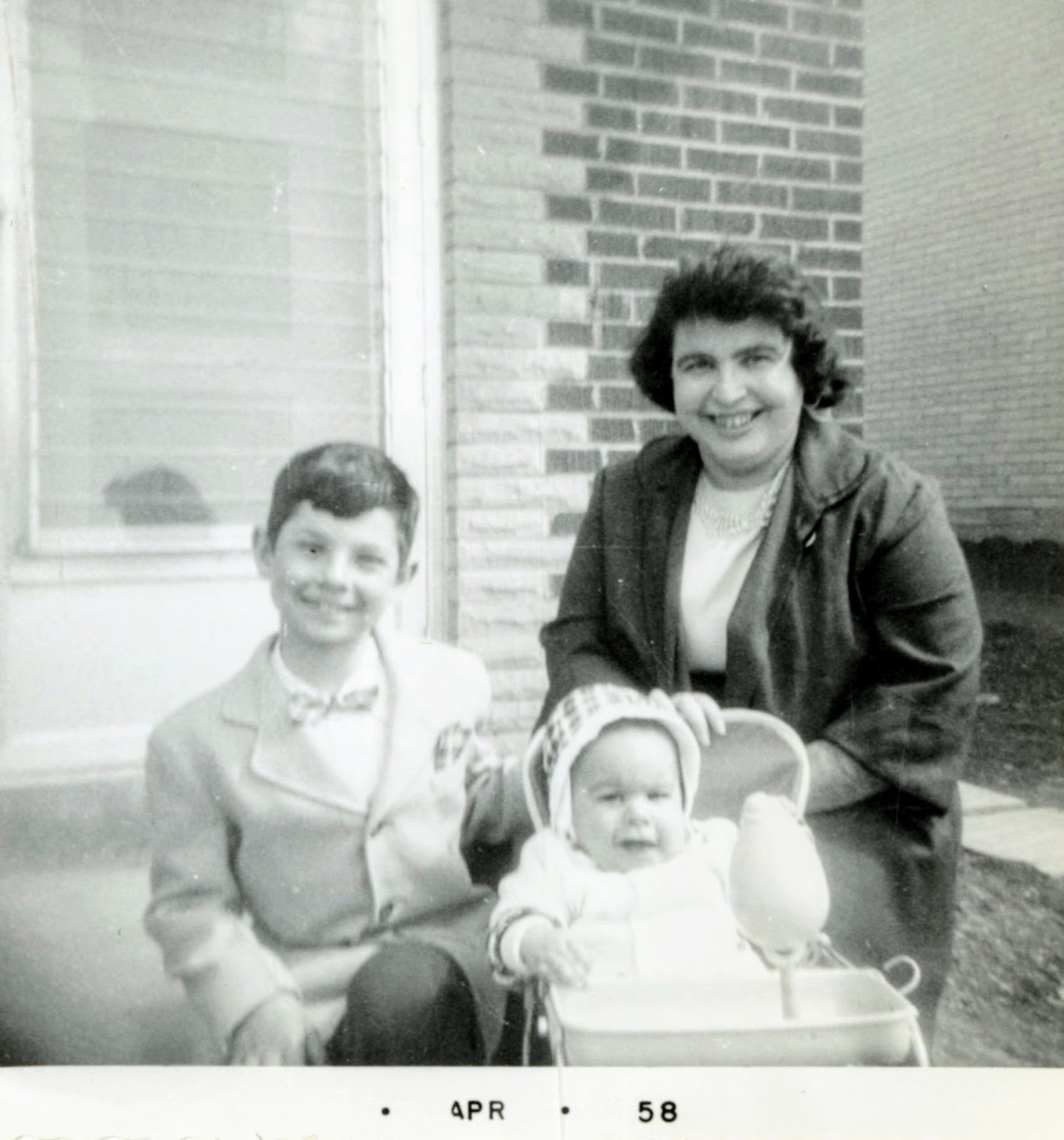

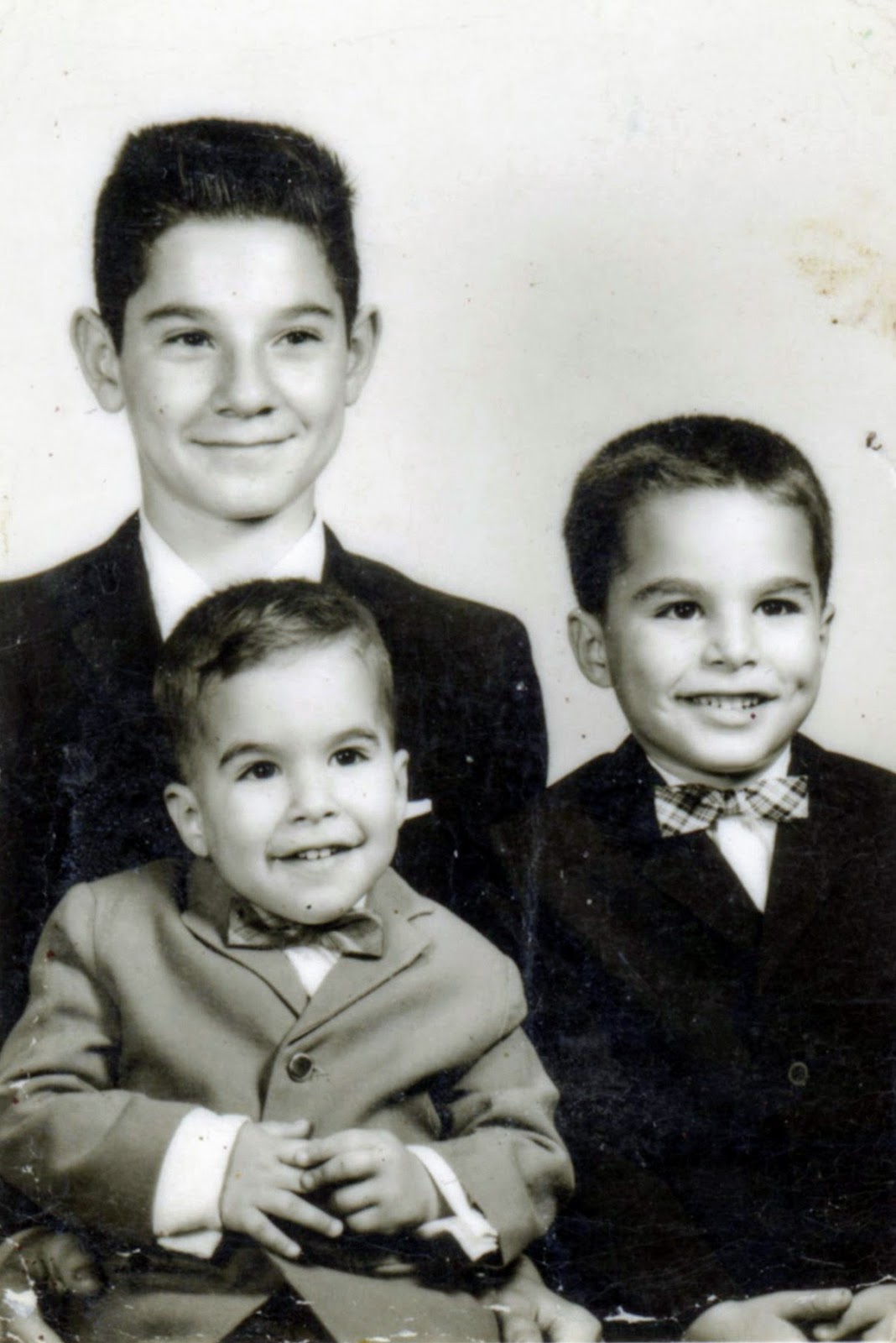

This will be the fifth major retelling of the Oz story over the course of 125 years. The 1900 book, The Wizard of Oz, and its successors were beloved to my mother in her childhood. The classic 1939 movie was first shown on television in 1956, the year before I was born. By the time I was old enough, in the 1960's, the annual telecast happened every February, and every kid I knew watched it raptly after weeks or months of anticipation. The Wicked Witch of the West was one of the scariest things I could imagine as a child.

Gregory Maguire's novel "Wicked," an underrated masterpiece, premiered in 1995, just after I took the plunge from Internet researcher to entrepreneur. I quickly came to realize that my enthusiasm for the technology was completely dwarfed by the greedy gold rush to exploit it, I met many captains of industry, and although a few were great people, most were more like Maguire's reimagined Wizard, cultivating an image of good while behaving quite otherwise. Maguire's reimagination of the witch as a misunderstood creature trying to do good in a world of evil wizards struck a deep chord with me. If you hear me describe the venture capitalists of Silicon Valley as wizards, know that this is more likely to mean they are humbugs and frauds than practitioners of any real magic.

I didn't get to see the 2003 musical until I went to work for Mimecast in 2010 and started spending a lot of time in London, but it was love from the start. One of the highlights of that decade for me was seeing Wicked on the West End over and over -- with my wife when she was in town, otherwise with local friends, and at least twice all by myself. It soon replaced Sweeney Todd as my favorite musical of all time. Give me half a chance and I will sing much of it for you myself!

Does it surprise you I got hooked, and all too soon?

What can I say? I got carried away. And not just by balloon

Then, as many of you know, my life got harder, and in the year of the pandemic I suffered many losses -- my daughter, my son-in-law -- and was preparing for my own massive open heart surgery. The song "As Long As You're Mine" will always be, for me, the story of my daughter's beautiful and tragic love affair and her husband's slow death from brain cancer.

And if it turns out it's over too fast.

I'll make every last moment last

As long as you're mine.

I listened to the soundtrack often that year, taking particular comfort from the notion, embodied in "For Good," that the people you love continue to shape who you are long after they are gone.

Like a ship blown from its mooring by a wind off the sea

Like a seed dropped by a skybird in a distant wood

But the worst year of my life was followed by the best period of my life, when instead of open heart surgery I started taking the then-experimental drug Camzyos, and was not merely restored to health but given the best health of my life. I had spent a year preparing for my own possible demise, so I suddenly found myself with no loose ends in my life, semi-retired, my finances and friendships in perfect order, but with more energy and better health than ever before. For the first time in my life, I felt like I could do absolutely anything I chose to do. My life was peaking, and the song that echoed through my brain was of course "Defying Gravity."

Something has changed within me. Something is not the same

I'm through with playing by the rules of someone else's game

Too late for second-guessing. Too late to go back to sleep

It's time to trust my instincts, close my eyes and leap

Since then I have started a company, written a book, returned part-time to academia, completely avoided the periodic depression that has haunted me since childhood, and generally lived my absolute best life in my 60's, when most people are simply hoping to reach a peaceful retirement. And when people ask me about it, I always think, and often simply say, "I am defying gravity."

I'm not someone who generally follows the entertainment industry, but as a fan of the musical I've closely tracked the unfolding of the movies, which took over 15 years to get made. As the plans soldified, John Chu was chosen as the Director, and the cast was fleshed out, my anticipation has only grown. It's going to be a cinematic epic -- they planted 9 million tulips just to show how the munchkins farm tulips for their colors! Some fans were upset with the decision to split it into two movies, but I was thrilled -- instead of compressing the story, they are expanding it to include more from the books. And there are new songs!

With each leak and preview, I've only grown more excited and hopeful that the movies will be a worthy next chapter in this long, glorious story. Now, with the first movie's release only weeks away, the early reviews are starting to come out -- uniformly glowing, with one reviewer calling it "the movie of the century." It is downright embarassing how excited I am.

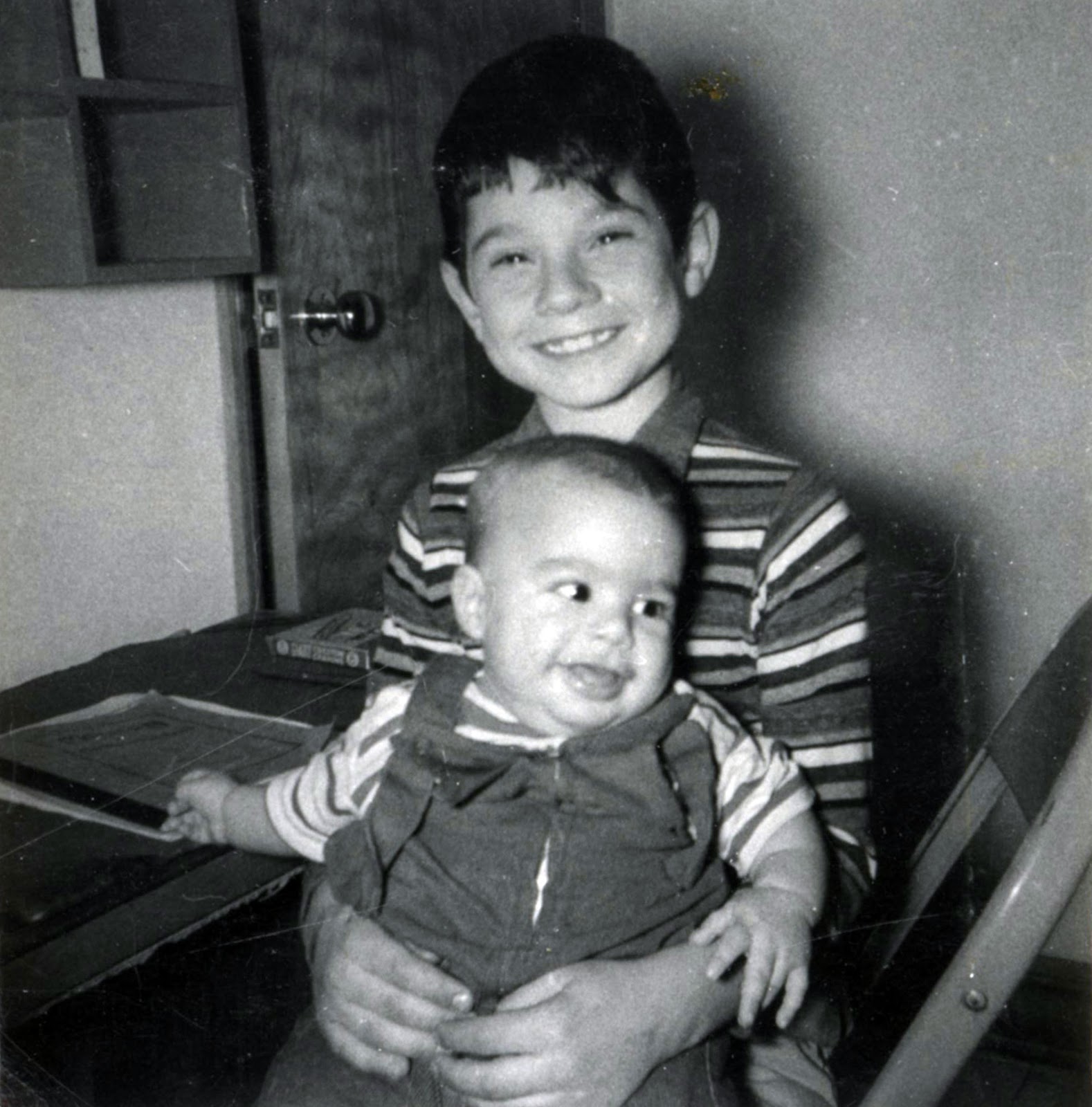

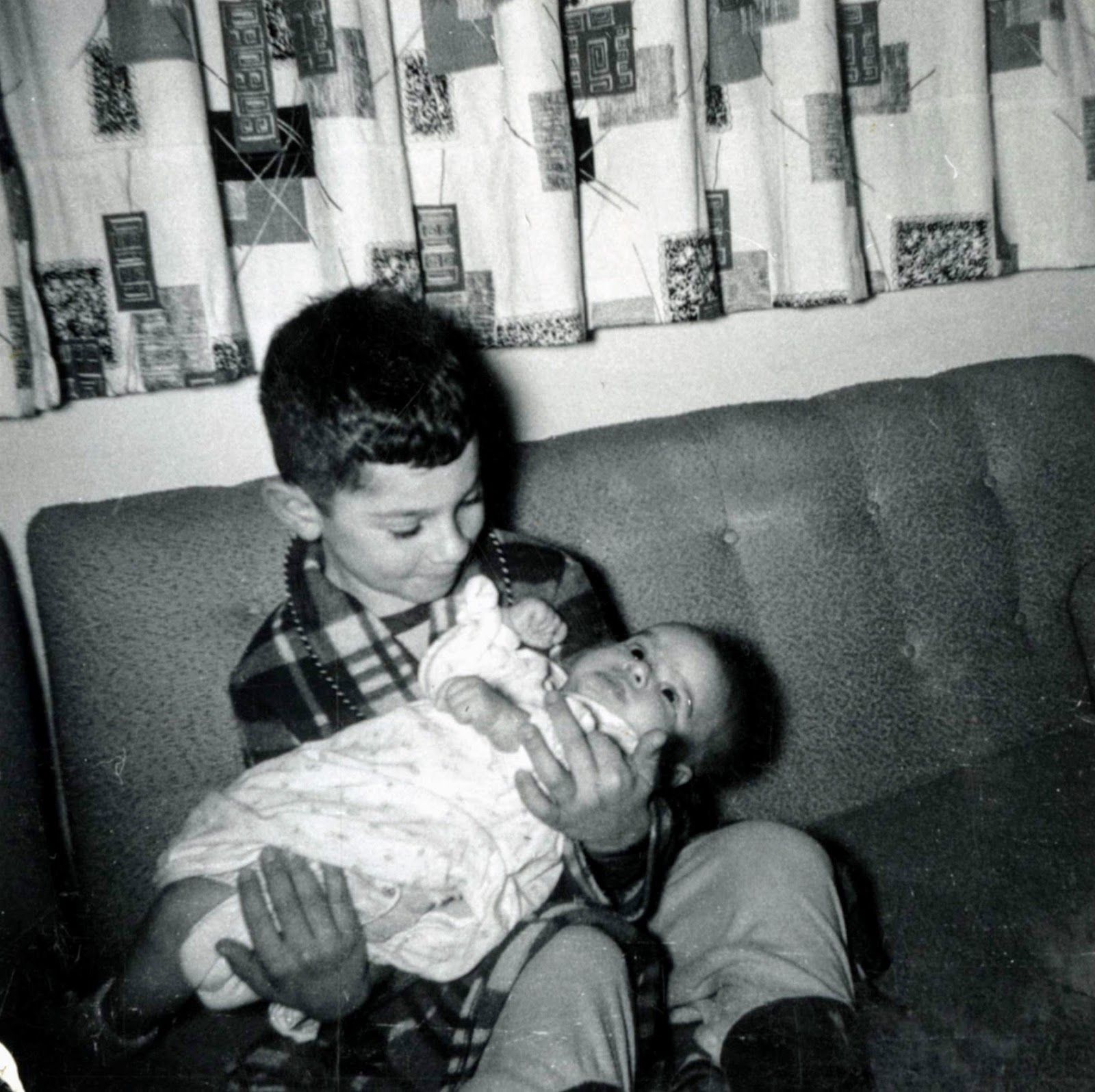

Wicked premieres in Michigan on Friday, November 22. I have tickets to take my youngest grandchildren, ages 3 and 5, to see it in IMAX on Saturday morning. Their introduction to this glorious story will be in its fifth incarnation, likely my last. I've also got a ticket to see it alone the night before, with nobody to distract me from the magic.

By the time I last saw Wicked on the London stage, the first measure of the overture was enough for me to feel the tears starting to well up. I can't begin to understand the magic of this story, or how L. Frank Baum (in whose honor Gregory Maguire named the witch Elphaba!) managed to start all of this in motion. But the story is always with me, like a handprint on my heart. It has changed me for good.

I can't wait!

[If you have an hour to spare for it, I highly recommend this excellent video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_NjQonmX8M

which tells the story of the politics and social impact of the Oz story, from the original books to today.]